Localisation is a hot topic on the global stage, but South Africa brings its own unique challenges and opportunities to the table. In this article, we’ll dive into these nuances and introduce a Localisation Framework designed to equip procurement and supply chain professionals with the tools they need to craft an effective localisation strategy.

Localisation in South Africa

In the South African context, localisation is often viewed primarily as a state driven policy tool. The Government’s stated aim is to use localisation policy to develop local industrial capacity, increase employment and increase competitiveness across the economy. This is given effect through the use of state procurement.

The policy compliance centric view of localisation can be an inhibitor. At its most basic, localisation, sometimes termed local sourcing, is the sourcing of products, materials or services within close proximity.

The global context that South African supply chains operate in is characterised by instability. Geo-political conflicts such as the wars in Syria, Gaza and Ukraine, piracy in the Red Sea and the diversion of shipping from the Suez Canal and the Strait of Hormuz have attenuated supply chains and significantly impacted commodity prices.

The import of goods is further exacerbated by deteriorating local import infrastructure. As an illustration, SA ports perform poorly in a global context, approaching the bottom of the World Bank’s Container Port Performance Index (CPPI) for both Durban and Cape Town. Over the November/December 2023 period the container processing backlog at the country’s largest port, Durban Pier 2, approached 4 months.

It is expected that the world will continue to experience more frequent, more severe and more impactful short-term crises going forward. Supply chain disruption and resilience must be seen as the new normal.

Leading organisations must explore alternative materials, non-traditional partnerships and compact supply chains. Localisation can be seen as a powerful lever to explore these opportunities.

What this article looks to investigate is not the application of state localisation policy to meet local content requirements or combatting higher import tariffs but rather the exploitation of localisation to manage supply chain risk and the identification of cost saving opportunities.

Developing a Localisation Decision Making Framework

Our recent engagement with one of South Africa’s leading quick-service restaurant (QSR) brands has not only highlighted the challenges of global sourcing but, more importantly, showcased the immense potential for localising key aspects of the supply chain.

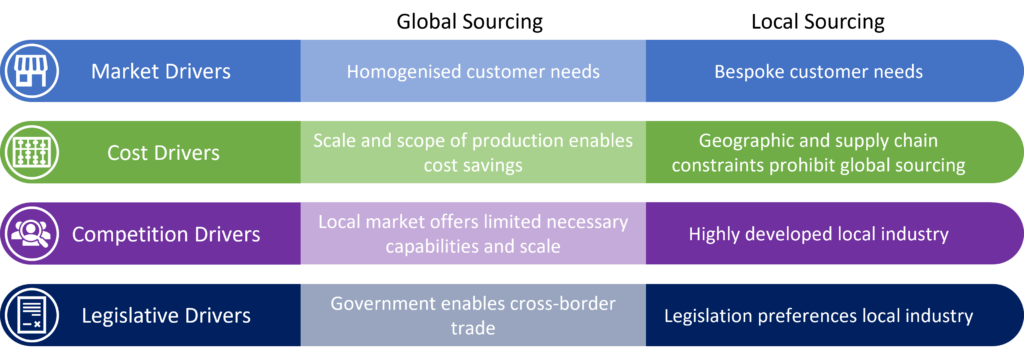

Our approach allowed us to develop a decision-making tool that objectively evaluates the opportunity to source locally, contrasting it with the conventional drivers of globalisation. Drawing inspiration from Yip’s Industry Globalisation Drivers, we formulated a framework that considers Market, Cost, Competition, and Legislative aspects.

Market Driver: This considers the end user/customer. The key focus is on understanding if there are unique requirements for the local customer/user.

Competition Drivers: This considers the state of competitiveness of the industry under consideration. The key focus is assessing local suppliers against global counterparts in terms of equivalent quality, consistency, and scale.

Cost Drivers: This considers the cumulative impact of cost. Items considered here include the financial impact of lead times, shipping, manufacture and forex.

Legislative Drivers: This considers if there are any regulatory or legislative barriers or advantages to source locally. This can include considering the transformation agenda and enterprise supplier development

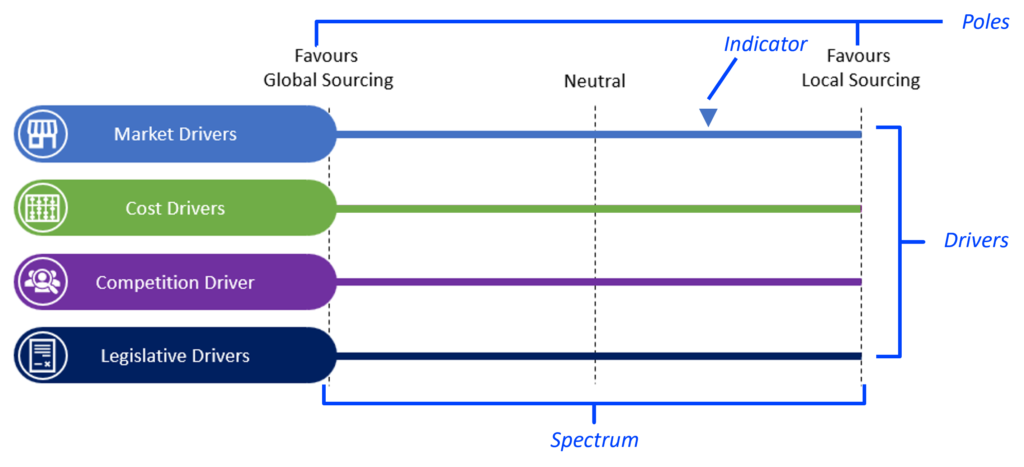

Global sourcing and local sourcing can be used as poles of comparisons.

Figure 1: Driver Summary

The client specific context is mapped to the four drivers identified and plotted on spectrum between favouring global sourcing or favouring local sourcing as per framework presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Localisation Framework

The framework can be used as a decision-making and communication tool that allows for an objective evaluation of the opportunity to locally source. The framework can be used by procurement as the foundation for developing a localisation business case.

To understand how the framework can be applied let’s use the QSR client as a case study.

Client Context:

Our client, with over 1000 restaurants in Africa, faced substantial challenges due to extended lead times for new equipment and inconsistent availability of spares. This not only impacted their current operations but also jeopardised their ambitious expansion strategy.

Back-of-house (BoH) stainless steel equipment emerged as a pivotal area for potential savings. We identified the robust South African stainless steel equipment manufacturing industry as a viable solution, aligning perfectly with the client’s stringent quality and performance requirements.

Recognising the need for a transformational shift, we initiated a comprehensive approach focused on localised sourcing and maintenance of in-store kitchen equipment and spares.

Market Drivers:

Unlike the universal customer needs driving globalisation, local markets often demand bespoke solutions. In our engagement, we witnessed the successful adaptation of standard items to meet the specific requirements of the South African market, striking a harmonious balance between universal specifications and bespoke adaptations.

Cost Drivers:

While standardisation offers scalability and cost advantages, the erosion of cost differentials due to factors like forex fluctuations, geopolitical events, and global crises can render global sourcing less favourable. Our local sourcing initiative significantly mitigated the impact of a 100% increase in forex costs during the evaluation period, demonstrating the resilience and cost-effectiveness of a localised supply chain.

Competition Drivers:

Assessing local suppliers against global counterparts, particularly in stainless steel fabrication, revealed a mature and fit-for-purpose local industry. Our benchmarking mechanism ensured that local suppliers delivered equivalent quality, consistency, and scale, validated through a rigorous prototyping exercise.

Government/Legislative Drivers:

Though limited in impact for our client, our localisation exercise presented an opportunity to contribute to their transformation agenda. Directing spend towards empowered local suppliers positively influenced the QSR’s BBBEE scorecard.

In essence, these identified drivers serve as critical considerations in developing a compelling localisation business case. Collectively, they represent the essential levers that procurement can strategically pull to enhance supply chain efficiency and resilience.

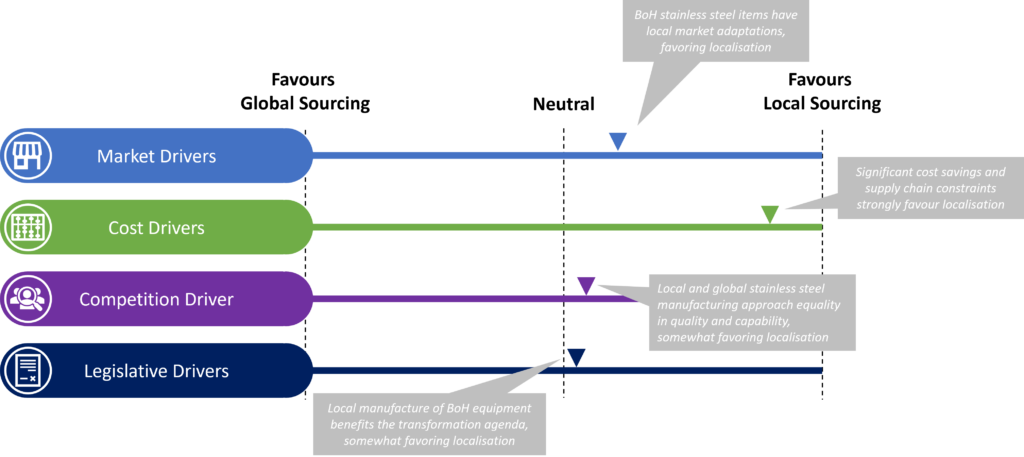

Application of Localisation Framework

Figure 1 presents an application of the localisation framework in the context of the QSR engagement. The client specific context is mapped to the 4 drivers identified and plotted on spectrum between favouring globalisation or favouring localisation.

- Market Driver: BoH stainless steel items have local market adaptations, favouring localisation.

- Cost Driver: Significant cost drivers and supply chain constraints strongly favour localisation.

- Competition Drivers: Local and global stainless steel manufacturing approach equality in quality and capability, somewhat favouring localisation

- Legislative Drivers: Local manufacture ofBoH equipment benefits the transformation agenda, somewhat favouring localisation

The outcome in Figure 3 presents a clear case for considering localisation for the QSR.

Figure 3: Application of the Localisation Framework

Key Lessons Learnt

In taking the local sourcing exercise from a business case to an implementable programme, several learnings stand out as important:

Any application of the framework needs to be underpinned by foundation procurement efforts such as spend analysis, market analysis and demand forecasting to appropriately understand cost baselines and influences.

Company sponsorship of the initiative is key. Localisation efforts involve many aspects of the business and can require strong leadership to adjust the status quo. Local sourcing efforts need to be considered as long-term strategic opportunities.

Relationship management with any incumbent suppliers impacted by localisation efforts must not be under considered. These suppliers can be invited to participate in the process or provide input into the initial analysis.

Many local suppliers were eager to respond but few could deliver the quality, consistency and volumes required. The supplier vetting process was extensive and time consuming. A sustainable fit needs to be preferenced in supplier evaluation.

Global standards were onerous for local market suppliers, they needed to invest time, equipment and capacity to prototyping. Being upfront on the effort and expectations is key.

Finaly, internal technical expertise in vetting and prototyping the output of local suppliers needs to be established early in any localisation process. This needs to be considered in resource planning or validated as an outsourced cost.

I would recommend that the Localisation Framework be used to guide the development of a localisation business case. It can be used iteratively, to set initial expectations and revised post detailed analysis. The frameworks acts as a clear communication tool laying the foundation for decision making.

References:

Avenyo, E., Bosiu, T. and Nyamwena, J. (2023). “Localisation in South Africa: Analysis of key emerging issues”, CCRED-IDTT Working Paper 2023/1.

Chartered Institute of Procurement and Supply [CIPS], (2024). “Local Sourcing”, Available at: https://www.cips.org/intelligence-hub/sourcing/local

Creamer, T. (2023). “SAAFF warns of rising port-congestion costs”, Available at: https://www.engineeringnews.co.za/article/saaff-warns-of-rising-port-congestion-costs-2023-11-22

Deloitte, (2022). “Procurement and Supply Chain Resilience in the Face of Global Disruption” Available at: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/uk/Documents/consultancy/deloitte-uk-procurement-and-supply-chain-resilience.pdf

Industrial Development Corporation [IDC], (2024). “Economic overview: Recent developments in the global and South African economies”, Department of Research and Information.

Lawfor, P. (2024). “Disruption and resiliency the new norm for supply chains”, Available at: https://www.investec.com/en_za/focus/economy/disruption-and-resiliency-the-new-norm-for-supply-chains.html

PWC, (2024). “South Africa Economic Outlook 2024” Available at: https://www.strategyand.pwc.com/a1/en/assets/pdf/sa-economic-outlook/business-value-creation-and-social-impact.pdf

Seymour, T and Oldfield, R. (2021). “Localisation is the New Globalisation”, Available at: https://digitaledition.strategybusiness.com/publication/?i=696981&article_id=3930641&view=articleBrowser

South African Business (2024). “Disruptions to supply chain on the high seas”, Available at: https://www.southafricanbusiness.co.za/04/2024/south-africa/disruptions-to-supply-chain-on-the-high-seas/

Yip, G. 1992. “Total global strategy: Managing for Worldwide Competitive Advantage”, Prentice Hall.