Insourcing provides workers with a “livable” wage, fringe benefits and opportunities which are seen as perks to employment in corporate South Africa. This assists workers to develop and progress out of their circumstances.

If done effectively, insourcing assists organisational stability, projects a positive public image and increases trust between both internal and external stakeholders. We investigated how this is achieved through working with a partner in the educational sector.

A balancing act between cost, risk and specific services

Effective insourcing requires careful and strategic decision making early on in the process. The temptation organisations face is to remove complexity and risk to the organisation by insourcing low skill, labour intensive tasks. However, these services can come at a high cost to the organisation, which has led to the perception that insourcing is purely a cost to the organisation with little to no operational benefits.

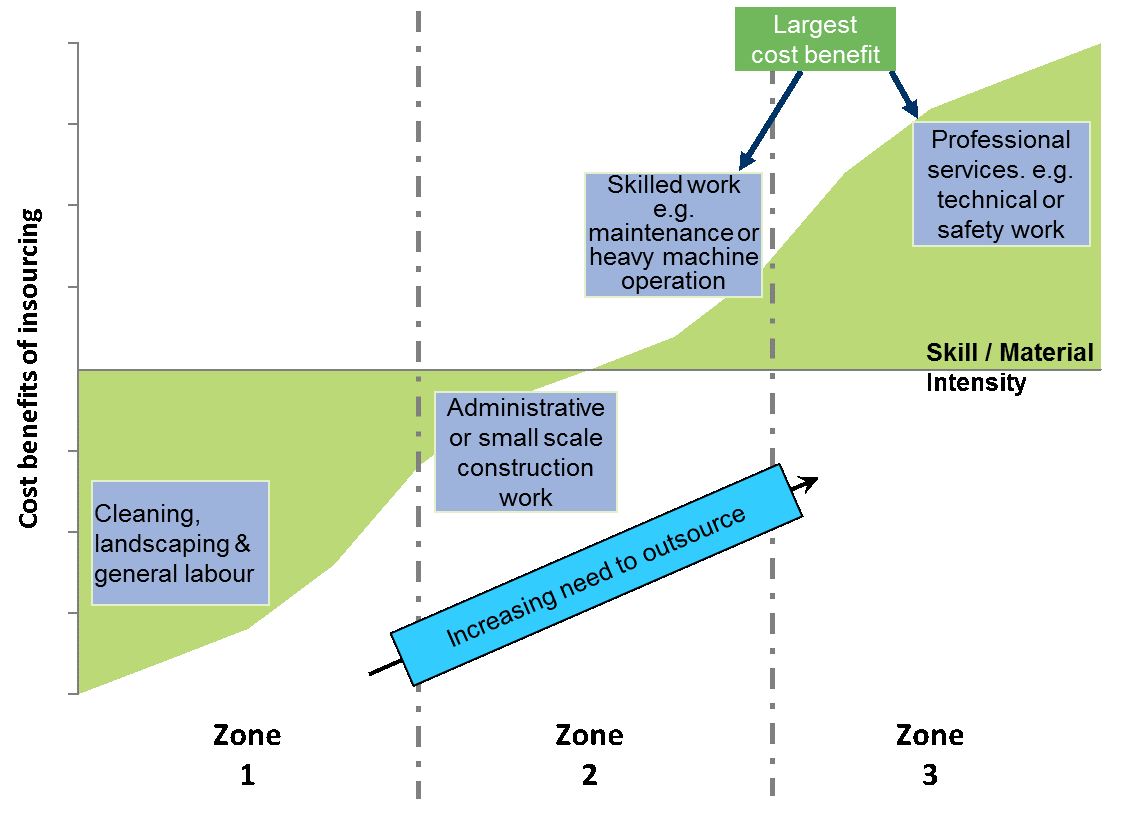

As depicted in Figure 1 below, we have found a direct relationship between the cost benefit of insourcing and the skill level of the workforce to be insourced. As the skill level increases, the potential for cost benefits increase while for lower skilled functions, cost benefits decrease (i.e. costs increase).

The rationale for this finding lies behind a few key factors. Low skilled workers tend to attract the lowest possible salary and have limited negotiating power due to the high unemployment rate within South Africa.

These workers are paid a bare minimum salary by their employers which is usually significantly lower than organisations grading scales allow for. This means that companies outsource and see a huge reduction in these costs while not baring witness to the real wages these employees end up working for. Converse to this is those with a higher level of skill (and potentially some form of certification). These workers are normally covered by an industry charter specifying minimum wage, and employers of these workers add significant margins on top of this rate in order to make profit.

To illustrate these two points, we can take an example of cleaning services compared to maintenance services. Cleaners will generally receive a salary of approximately R3000 per month. Whereas a maintenance worker (well paid with skills) may receive up to R18,000 rand per month.

For cleaning services, a company will pay between R4000 and R5000 per month per worker while maintenance services will equate to an hourly rate of up to R450/hour (resulting in R75,600) per month. To insource a cleaner will result in additional costs of up to R2500 per month, while savings of above R57,000 can be made in insourcing a skilled maintenance worker. This, of course, carries the caveat that an organisation would have to have sufficient work to occupy this worker on a full-time basis.

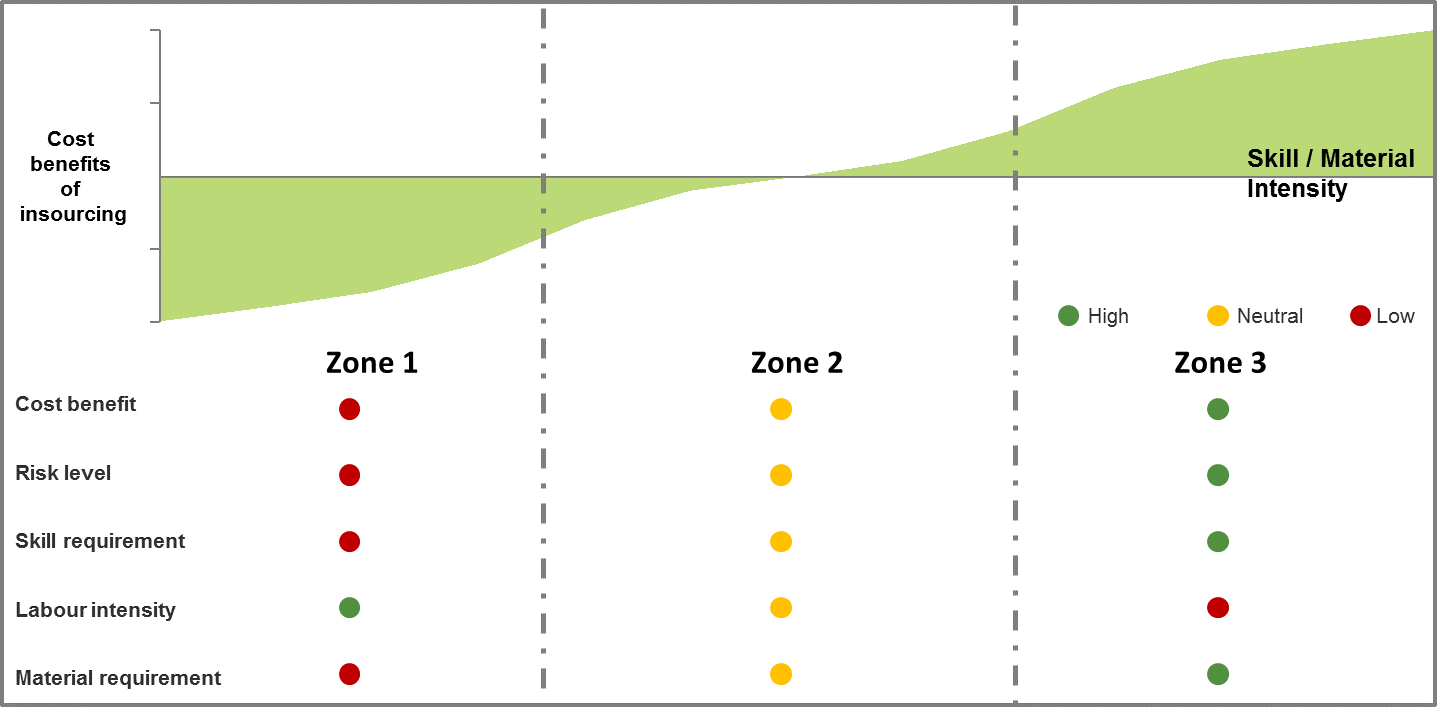

In addition to the costs associated with insourcing, it is important to consider risk exposure, demand for a service, skill availability, start-up costs and operations costs. The risk exposure that an organisation is willing to take on is a key proponent to determining how much of the highly skilled work it will be willing to insource. Highly skilled work (i.e. high voltage electrical work) or safety related work (i.e. fire equipment maintenance) are associated with higher risk; while less skilled work such as cleaning and security are associated with low safety and liability related risks. A decision must be made by organisational management as to the risks they are willing to absorb when insourcing different services.

The demand for a service or the frequency with which a task is performed, needs to be understood as it is an important consideration in defining the services which will be insourced. A seasonal task like ‘providing security for special functions’ is unlikely to be successfully insourced as there will be significant periods of downtime for these workers, whereas ongoing tasks such as cleaning or front of house security provide a constant demand and thus a constant employee requirement. Scheduled tasks such as building equipment servicing or inspection may be worth insourcing based on the frequency and number of tasks that are required.

Skill availability of those available to be insourced should also be analysed to determine whether the required skills are readily available. If the skills required to perform the envisaged insourced tasks are not present within the pool of eligible employees, obtaining these skills externally may incur additional costs can cause further dissatisfaction in those to be insourced.

Costs associated to insourcing are important to consider when selecting services to be insourced. Start-up costs including administrative, infrastructure, and equipment requirements to perform the envisaged tasks inhouse. Operational costs, including the costs involved in having the required management structures and the day to day expenses associated with uniform, consumables and equipment wear and tear must be considered in informing the insourcing decision.

Taking the above into consideration, a strategic decision should be made in order to balance skilled tasks with unskilled ones to balance additional costs with potential cost savings. Zone 2 in Figure 2 below should be the target zone for organisations to minimise the costs of insourcing.

Additional Cost Considerations

The cost benefits of insourcing can also be realized in the economies of scale and strategic supplier partnerships which can be formed with being a bigger organization that is consolidating the functions of several smaller service providers. Some of the other major cost benefits that are associated with insourcing are the use of shared functions (like admin, HR and procurement), shared resources (like the leveraging off existing management and support staff) and shared spaces (existing offices and infrastructure). These are costs that will no longer fall into the margin that outsourced service providers have to cover currently.

Apart from the cost benefit, there are several other cost implications to be considered. As depicted below, the wage bill associated with insourcing is perceived to be astronomically high as people tend to compare the ‘wage that workers earn while working for the service provider’ with the ‘potential wage they could earn if they are insourced’. This is however not a like for like comparison and organisations should rather compare ‘the overall rate per employee charged by the service provider’ with the ‘wage of the insourced worker’. This comparison shows that the price paid by the insourcing organization per worker is not as high as initially perceived.

Determining the insourcing mechanism depends on the organisational context

It is important to consider the extent to which one would like to insource. Indirect insourcing, also referred to as the top-up model, involves increasing the rates paid to the service provider and mandating them to increase the worker wages up to the acceptable or liveable wage. The advantage of this model is that it is relatively simple to implement and manage. The main disadvantage to this model is that it purely adds cost with no potential of achieving operational savings. Furthermore, it can also blur the lines as to who the real employer is, as the outsourcing company is taking operational decisions based on its clients demands. Workers may also have fewer benefits compared to working directly for the organisation such as access to services that are available to all direct employees (education as an example in the case of Universities).

The Hybrid model, involves the insourcing of certain tasks and the outsourcing of management and/or other functionalities. The main advantage of this model lies in the fact that it achieves social justice with a lower administrative and HR burden than when compared to full insourcing. If this model is selected, the cost benefits discussed earlier can be optimised from the onset of the insourcing project. The main disadvantages hereof are that worker satisfaction with the process is low (since only partial insourcing has occurred) and the difficulty in the management of the interface between the work to be insourced and that which is to be outsourced.

The 100% insourcing model involves the insourcing workers required and elimination of a requirement for external service providers. The main advantage of this model lies in it generating more worker satisfaction and buy-in than the other two models. This model also creates more accountability and ownership for tasks as external service providers tend to be “at arm’s length”. The biggest disadvantages of this model are that it requires strong and proactive management of both the employees and equipment or materials, it can be administratively intensive, and some of the skills required to manage the new employees may not be readily available (specifically skills of a technical nature).

Insourcing life cycle

The insourcing life cycle typically consists of the three phases: planning, implementation and stabilisation. The planning phase is characterised by (and may only be a success through) a significant amount of stakeholder engagement and strategic decision making. Some of the key steps in approaching this phase are the objective establishment of the insourcing requirements and the ensuring of extensive stakeholder engagement and education.

In the implementation phase, systems, processes, procedures and support services are put in place to ensure the success of insourcing. It is upon completion of these activities that employees are moved to the new organisation. When approaching this phase, some of key steps include the creation of mediated forums to ensure continuous dialogue and feedback amongst the various stakeholders, the clarification of roles and responsibilities, the establishment of support infrastructure, the modification of systems and the development of processes, procedures and controls to ensure continuity of service levels into the stabilization phase.

In the stabilisation phase, with new employees on board, systems, processes and forums are tweaked or created to deal with exceptions and to bring about efficiency improvements. This step is best addressed through the creation of additional procedures, processes and forums and the adjustments to the existing systems to ensure full integration between the work requirements, performance management, consumables management and financial systems.

Additional Considerations

Throughout the process of managing the insourcing life cycle, many of the pitfalls can be averted through using and easily understandable, transparent an objective (data driven) approach. Regular communication and strict adherence to promised deadlines is also essential to gain the trust of all the stake holders. Stakeholders (especially middle managers) also need to be deeply involved in the creation of processes and the selection of the workers they will working with. The involvement of the lower levels (through the middle managers) also assists in creating the required momentum to carry the required actions well into the stabilisation phase.

Constant on the ground management and measurement is required to ensure that the organization manages the workload and understands the costs associated and as such can change the operating model to ensure the correct number of people are insourced as well as costs being effectively managed. Insourcing is a complicated process that needs to be effectively managed to deliver the required value. If effectively managed, insourcing can maintain the organization’s bottom line while improving its brand image among its stakeholders and in the market place.

To learn more, contact our Supply Chain, connect with our staff on LinkedIn or call 011 233 0000.